Part 1

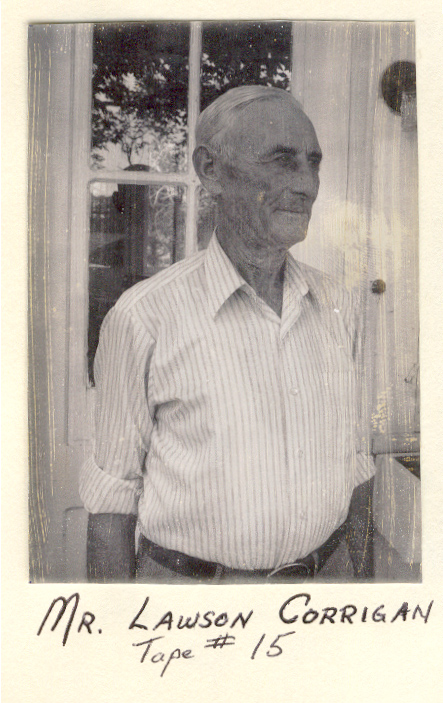

Mr. Corrigan: “My full name is quite a long one: William Victor Lawson Corrigan.”

Date of birth: August 16, 1894

Interviewer: “Were you born in Clarendon?”

Mr. Corrigan: “I was born in Clarendon, on the Corrigan farm just below Shawville where we lived after we were married for a while.”

Interviewer: “So you’ve lived all your life right in this area around here?”

Mr. Corrigan: “Well, except for short periods I’ve been away. I lived in Cobden when I was a young chap. For a couple of years I went on a train from Cobden to Renfrew to go to school back in 1910 and 1911. I bought a ticket good for a month, and it cost you five cents a trip from Renfrew and Cobden for school, for students.”

Interviewer: “Could you give us your father’s name?”

Mr. Corrigan: “William Corrigan.”

Interviewer: “And his date of birth, if you know it?”

Mr. Corrigan: “I don’t know his date of birth. I know he died in 1903.”

Interviewer: “Was he born around here?”

Mr. Corrigan: “Yes, he was born on the same property I was born on, exactly the same place. His father emigrated over here. Part of the family was born there, and part of it was born in Clarendon. My grandfather was a master of Shawville Lodge, Orange Lodge. And he was also the first warden of Ottawa County, which was Pontiac County. My grandmother was a Hodgins on my mother’s side. And my mother was a McDowell.”

Interviewer: “What was your mother’s name?”

Mr. Corrigan: “Sarah Ann McDowell.”

Interviewer: “And who were your grandparents again?”

Mr. Corrigan: “Thomas Corrigan and I think it was Ann Armstrong; I’m not positive of her name. And Long William McDowell, and his wife was a Hodgins, and I don’t remember her name.”

Interviewer: “Were they all farmers?”

Mr. Corrigan: “Oh, yes.”

Interviewer: “Could you give us the names of your brothers and sisters?”

Mr. Corrigan: “I had three half-sisters. I had no brothers. My father was married twice. His first wife was an Armstrong. My father’s sister was married to a Hodgins. And his family, one of ’em married a Scully.”

Interviewer: “Where did you go to church? What church did you attend?”

Mr. Corrigan: “My mother was a Methodist. My father was an Anglican. We used to go to this Knox’s Hall that everybody in the country went to. They went to their own church in the morning and Knox’s Hall in the evening.”

Interviewer: “Where was it?”

Mr. Corrigan: “Oh, this was back in the early 1900s. The Holiness Movement had meetings there. This was a community hall built by the community and designated by William McDowell for religious purposes. No denomination, so everybody around the district used to go to it, and we had a Sunday school. On Sunday night the Holiness Movement people had meetings there for their members. They built a church up near Radford and then moved down to Shawville. And then they had Knox’s Hall.”

Interviewer: “And where was Knox’s Hall?”

Mr. Corrigan: “You know where the Lodge Room is down there? On the old highway? It’s about two miles from Shawville. That’s where my school was. Knox’s School.”

Interviewer: “What school number was that?”

Mr. Corrigan: “Four.”

Instructor: “Do you remember who your first teacher was?”

Mr. Corrigan: “Yes, Mabel Armstrong.”

Interviewer: “That would be a one-room schoolhouse?”

Mr. Corrigan: “Oh, yes.”

Interviewer: “What sort of subjects would you take?”

Mr. Corrigan: “History, geography, arithmetic. We had Canadian history, writing, spelling, of course.”

Interviewer: “Do you remember anything exciting that happened in school?”

Mr. Corrigan: “Yes, I remember a bunch of us went down to the creek when it was cold, and we were by a tree and we all sat up on it. And when I was coming down there was one fellow snipped the branch and I was holding it, and it snapped, and I fell down and pretty near killed myself. I remember that all right!”

Interviewer: “How many kids would there be going to school in that schoolhouse?”

Mr. Corrigan: “There has been as high as sixty. The bigger boys went in the wintertime and stayed home and worked in the summertime. The younger fellows were supposed to go all the time, but sometimes the snow was too deep. There was no snowplow then.”

Interviewer: “You all walked to school?”

Mr. Corrigan: “I walked.”

Interviewer: “Did you have very far to walk?”

Mr. Corrigan: “Yes, it was about a mile-and-a-half.”

Interviewer: “Did you have to learn to recite poetry and things like that?”

Mr. Corrigan: “Yes.”

Interviewer: “Did you go to school in the old Academy?”

Mr. Corrigan: “No. I went to Renfrew Business College, then I took a year at MacDonald College, and then the First World War ended that. I was lucky enough to get through. I never got back.”

Interviewer: “And so you’ve been farming ever since?”

Mr. Corrigan: “They put me on a farm. They had tribunals the first year I got back. You were examined–there was a medical man who came up here and examined everybody–and we lived on a farm. I hadn’t been working on the farm, but the tribunal ordered me to go back to the farm.”

Part 2

Mr. Corrigan: “That’s what you done. So that’s what started me to farm. I took a business course at Renfrew, and I started to work in G.F. Hodgins’s store in 1912. It was a very big store.”

Interviewer: “About how much would you earn working there?”

Mr. Corrigan: “Fifteen dollars a month.”

Interviewer: “Fifteen dollars?”

Mr. Corrigan: “Yeah. You people don’t realize what things cost. Things were different then. That’s what I got for the first six months. And that’s about what you got coming in the back door. It was considered a white-collar job. Then I got forty dollars. That’s what I got on the side. I drove a horse and buggy.”

Interviewer: “How long have you been at this farm?”

Mr. Corrigan: “Since 1926.”

Interviewer: “Was the house built then when you came here?”

Mr. Corrigan: “Yes, I was born here. When my father retired he wouldn’t sell the farm. He insisted that I work it. I worked both places for a while. Then I built the house in Shawville, moved down there, and then moved up here and sold the other house.”

Interviewer: “So about how old would the house be?”

Mr. Corrigan: “Somewhere between eighty and a hundred years old.”

“I exported a lot of cows. I sent cows over to the States. You had two governments to deal with–the shipment to the States to deal with their regulations and the Canadian Government. Each cow had to have a health charge, a veterinary tester, blood samples. It took seventy-two hours to test the blood, and then send the report back to the veterinary for the Government. It had to be signed by one of the veterinaries in the health department before you could ship the cows. And during the War you had to have a signed form from the bank. You couldn’t ship with Canadian money; it had to be American money… So quite a lot was entailed.”

Interviewer: “What crops did you grow on the farm then?”

Mr. Corrigan: “Well, first I grew wheat, but then you couldn’t grow wheat. Oats and barley. Later I grew corn. We used to grow five or six acres of potatoes, which was quite a few potatoes at that time. Later I grew corn, silage, got a bigger garden. Shipped milk. Shipped cream, of course. Started takin’ it up to the creamery.”

Interviewer: “Do you remember anything about the old mill that was down in town where they built that new park?”

Mr. Corrigan: “Well, it wasn’t there in my time, but there was quite a big house there. William Hodgins operated it at one time.”

Interviewer: “Was it a flour mill?”

Mr. Corrigan: “Yes, I think they made flour with the stones, but I may be mistaken. Then there was Hodgins’s carding mill down on the other creek. That’s where we brought our winter supplies. In the old days you had sheep, and in the spring you killed the sheep and washed the wool in the creek and put it out in the grass to dry, and when it got dry there’d come a shower of rain, and you’d have to put it out again to dry. And then the women would take it to the carding mill in the fall. Some women got it made into rolls and spun the yarn, but my mother generally traded it for goods. You’d get what they’d call [‘?’]; you’d make underwear out of that. And yarn. And Andrew Hodgins had a big stock of dry goods there; you could get nearly anything. You’d get a chest of tea and a bag of sugar. They had their own flour. All they had to buy in the winter then was coal oil. You carried water in, electric lights. Oh, it was a better community experience than it is now. Somebody’d be at your house, or you’d be at somebody else’s house every night in the week.”

Interviewer: “Do you remember anything about George Caters?”

Mr. Corrigan: “Yeah. If there was an affair on or a picnic on, George’d have water that he got down at the spring, he’d have it in a barrel, and he’d charge you two cents a glass. ‘Course it was very warm from sittin’ out in the sun. You’d buy a bottle of pop for a nickel. Buy a package of six cigarettes for five cents. So things were a bit different.”

“And I guess maybe I was one of the ones that operated the first service station in Shawville. At G.F. Hodgins’s store there was about six cars in the whole district. There wasn’t any cars here until about 1907 or 1908. Then there wasn’t any until about 1910. The only place you could buy gasoline was at G.F. Hodgins’s. It came in drums. You’d measure it with a gallon measure, you had a big funnel, you put a shammy in the funnel, and drained it out through the shammy.”

Interviewer: “And how much would gas cost then?”

Mr. Corrigan: “Twenty-five cents.”

Part 3

Interviewer: “The people around who didn’t have cars, did they look up to the people who did have cars? Was it a big thing to have a car?”

Mr. Corrigan: “Oh, it was a big thing, but I don’t think they looked up to them. You’re goin’ along the road in a car, and there’s a fella he’d be out holdin’ the horse by the head and sometimes he’d jump the fence. No, I don’t think they looked up to them. They didn’t like them pretty well.”

Interviewer: “Do you remember the Russell House?”

Mr. Corrigan: “Oh, yes.”

Interviewer: “What was it like?”

Mr. Corrigan: “When old Mac McGuire run it, he and Chris Caldwell were two of the strictest hotel men in the old district. If anybody got drunk, they’d put them to bed and wouldn’t give them any more. Cut them off. They run a very strict house. But I remember when you’d get a meal at the Russell House and the Pontiac House for twenty-five cents. Everything was on the table in front of your face. It was put on the table, and you served yourself.”

Interviewer: “Were there different types of people who went to the Russell House rather than the Pontiac House?”

Mr. Corrigan: “I don’t think so. I don’t think there was much difference.”

Interviewer: “The local people didn’t favor one?”

Mr. Corrigan: “Both of them had big sitting rooms. They had these bar room chairs, you know, these round chairs, and in the evenings everybody could sit around and smoke and chat, and it wasn’t that bad. Sometimes someone would get a little drunk. If Chris Caldwell got a little cross, he [the customer] wouldn’t go there, and he’d go to the Russell House. And maybe just the opposite way. If McGuire got cross with somebody, he [the customer] wouldn’t go to the Russell House. George Caters, he used to get tight. One time Mr. Naylor was the Anglican minister, and he met him on the street and said, ‘Drunk again, George!’ And George said, ‘Me, too, Mr. Naylor!’”

Interviewer: “Both the Russell House and the Pontiac House had rooms?”

Mr. Corrigan: “Oh, yes. And both of them run a bus that met the trains. There were four trains every day here. Two down and two up. The morning train left about half past seven, between that and eight o’clock and came back up in the evening around seven or seven-thirty. Another train came up at half past ten and went down around three. And the buses met them trains; both the Russell House and the Pontiac House had buses to the train.”

Interviewer: “Do you remember when the Russell House was burned?”

Mr. Corrigan: “Yeah.”

Interviewer: “Was just the Russell House burned, or were there other places right around it?”

Mr. Corrigan: “Oh, no, there was quite a few places. Charlie Wakeman had a blacksmith shop right there, but there’s nothing of it now. It was right on the corner where Hayes’s is there. Where Hayes’s is, that was part of the Russell House stables. I guess the place across the road was burnt down, too. You know where the JR store is? George Hynes had a house there. There used to be a drugstore where the JR store is. (Clock chimes…) “They sold buggies, cutters. They had a horse there, an artificial horse harnessed up at the shop against a buggy standing there the way they show cars off now.”

Interviewer: “What about the sash and door factories?”

Mr. Corrigan: “Well, I guess McCredy was the first one. And later R.G. Hodgins.”

Interviewer: “Where was the first one?”

Mr. Corrigan: “Well, it was near the location where it still is, where Morley’s is there. And then John G. Elliott had a sawmill where the telephone office is, where the old theatre is. And there’s an old building there where old man Beckett made wagons and sleighs, Jack Beckett’s father.”

Interviewer: “Do you remember cheese factories?”

Mr. Corrigan: “Oh, yes, the old Lily cheese factory. Down right beside where we lived. The Lily cheese factory was just down the road. That was a big factory. Quite a process. There were ten or twelve teams coming in with a load of milk. No trucks, just horses. And you’d see a fella comin’ over the hill out where we lived and another fella comin’ over the other hill, and they’d start to see which could get to the factory first ’cause whoever got in first got unloaded first. Then they loaded ’em out and ran to the whey tank and filled up and took so much whey–they were supposed to get so much whey… “

Part 4

Interviewer: “What about the brickyards?”

Mr. Corrigan: “There were two brickyards. One there, Armstrongs had a brickyard. There’s nothing there now.”

Interviewer: “Was that down the brickyard road?”

Mr. Corrigan: “No, that’s down the highway. And there used to be two houses there and a stable. I remember when they made brick with horses and a machine. The horses went round and mixed up the clay and put it in the bowls and they took them out, and then later they got a steam engine, and they had a sawmill. Ralph Hodgins had a brickyard. There were ten or twelve men working in each brickyard in the summer.”

Interviewer: “Is there any story that sticks out in your mind about Shawville? Could you tell us a couple of them?”

Mr. Corrigan: “Well, I can tell you the time that Mike Murphy shot two boys. I think it was the tenth of April of 1910. Harry Hobbs and Harry Wilson and myself were fishin’ down at Armstrongs down at the river that night, and I can remember one night there they had Mike shut up in this little [?]–that’s where the fire station is now. The town had ordered him to get out. He used to be up at this end of the town. And Bill Dale, one of the fellows that was shot, was off to get feed for his horses, down where they used to have a gym and a dining hall and the old exhibition hall. These lads had been down there that night, down for a walk… There was an old log house there that the Armstrongs owned and had taken the front out of it and used it for a machine shed. Some of the lads seen Mike comin’ and said, ‘Mike’s comin’ with a gun.’ And they started runnin’ out and then turned the other way and his old muzzle blew out, and there were some forty shots taken out of Harry Howes and many out of Bill Dale. They were all a respectable bunch.”

Part 5

Mr. Corrigan: “There was eight of ’em all told.”

Interviewer: “So they weren’t just boys, they were fairly older?”

Mr. Corrigan: “Yes, they were all older. They weren’t doin’ anything. They were all respectable. Very respectable.”

Interviewer: “Do you remember anything of the fire of 1906?”

Mr. Corrigan: “Yes. That was at the upper end of town.”

Interviewer: “Were you in town then?”

Mr. Corrigan: “Yes, I was in town. I was comin’ from school, and I seen the fire, and I went out to town. It burnt from the United Church to the grist mill on that side and then from…[inaudible] and up to the garage on the other side.”

Interviewer: “How would they fight a fire back then?”

Mr. Corrigan: “Just get all the water they could and throw it out.”

Interviewer: “Sort of like a bucket brigade?”

Mr. Corrigan: “Like a bucket brigade; that’s all they had. They saved the garage right alongside [the Pontiac House]… I remember when we used to skate at the rink there in the wintertime.”

Interviewer: “Who ran it?”

Mr. Corrigan: “Well, it was different fellas. Armand Dagg used to run it. Jack McCollum was the architect I guess. Jack had the names in the Pontiac House. All the businesses put money into it, bought shares. I don’t think they ever made any money out of it; I guess they lost it.”

Interviewer: “What other activities would you do in the winter?”

Mr. Corrigan: “When I used to work in Shawville there they had what you called the Good Times Club. And we had the Orange Hall up, and we had a dance every week just local in town. The Orange Hall was a two-story building, and we had a story rented, and we used to take dancing lessons. Professors come up in the spring, and we took dancing lessons. It was run entirely different. We’d invite ones from Bryson, Portage, oh, a select bunch. It didn’t cost anything to come to our dances; we were the hosts. And then they’d invite us back to their dances. I remember they put on a ball at Portage when they were buildin’ the railroads, and they had it in the spring. The roads were that muddy that I wouldn’t take my own horse. I had a livery horse. Some of the boys got long-tailed coats, all the fellas that worked at the bank. I had forgotten. The rest of us were just ordinary kids; we couldn’t have that. So they put on quite a spread I tell you.”

Interviewer: “You’d go on sleigh rides, too?”

Mr. Corrigan: “Oh, yes. Lots of snow. All over the country.”

Interviewer: “Would you have horses on your farm when you were younger?”

Mr. Corrigan: “Well it was the only thing you had to work with!”

Interviewer: “No, no, but a lot of them.”

Mr. Corrigan: “Well, we didn’t ride much at that time. We drove ’em.”

Interviewer: “Where did you show your first one?”

Mr. Corrigan: “At the Shawville Fair. That’s an old fair; that’s a hundred.. I don’t know how many years now. It was long before I was born.”

Interviewer: “Can you tell us what the Fair was like?”

Mr. Corrigan: “Well, of course they didn’t have as good stock in that time, but the Fair was quite a good fair. They had a lot of good horses. That was one of the main things because horses was your main way of makin’ a livin.’ It used to become quite a competition. There was George Hynes, Chris Caldwell, Ernie Smiley, Jack Hamilton–he was in later–and it was quite a competition showin’ horses. One was always tryin’ to beat the other one. I remember when Larry was a young fella George always kept a good team; he used to run the horses, and he’d buy’em, too. So he was gettin’ Larry ready to show horses. Somebody had an air-tired buggy–it was a high buggy with wire spokes and air tires–and they couldn’t get the tires for it. The tubes were all wrong. A fella’d patch the tires–Tom Scully was patchin’ tires, and Larry was drivin’ around with the horse. So finally George got tired of that, and Dr. Lyons had a very fancy buggy, the nicest one in the country. George went there and asked the doctor if he’d let the buggy go and sell it. Anyway, he bought the buggy, and he bought two muskox ropes along with it, and he threw the ropes in the buggy. George drew the buggy up to where he lived at that time, so Larry had a good buggy for a long time. George Prendergast had a good road horse Larry got and he heard about a mate up at Pembroke, so they hitched the team up and drove to Pembroke, bought this horse and brought it home. Then John L. Hodgins got a very good team; he was asking quite a price. George bought the team; for five-hundred dollars he traded to George. Larry had one of ’em. Larry used to go out showin’ in Ottawa. He used to drive ’em down and drive’em back.”

Interviewer: “How long would it take to drive them down to Ottawa?”

Mr. Corrigan: “Well, they were mighty fast, but I don’t know how long he spent.”

“G.F. Hodgins handled butter, eggs, dressed beef, dressed pork, wool; he handled the cement for the bridge for the railroad over the river there to Portage. Big business.”

Part 6

Interviewer: “What do you think is the biggest difference between life today and when you were a young boy?”

Mr. Corrigan: “Well, of course everything has changed, even since I quit farming. The machinery. There wasn’t too much machinery. I mean we worked harder in some ways. I think we had a more social time. I don’t think the younger generation are doing that much different than we do. Of course, they have cars. They can go anywhere now. We didn’t have cars; we had to stay pretty well in the same place.”

Interviewer: “Do you think people are just as happy now?”

Mr. Corrigan: “Ah, that’s a good question. We’re quite happy. But I think there’s more happiness in the old days than there is today. Now you take for instance the Depression years. In the town of Shawville there was nobody on relief. There were few families that had to be helped out, but I think maybe one family in the whole district. This is a wonderful country and a wonderful class of people. You don’t find people like this in other countries. I’ve travelled around a little bit. People are different. Of course, the one thing about it, they’re pretty all near related!”

“Anyway, the town of Shawville, you see… Bristol, Portage du Fort, and Bryson were growing concerns before there was anything in Shawville, and Shawville went ahead, and they went back! It must have been the class of people doing business that built it ’cause there was nothing else they could grow. People must have been very energetic to keep everything going. Of course years ago it was altogether different. There were five blacksmith shops, sometimes there were two harness shops, the sash and door factory, the sawmill–generally there were two sawmills, not always, but as long as I remember, two brickyards, so it was quite industrial. Good bricks sold for ten dollars a thousand.”

Interviewer: “You were talking earlier about the Lily Cheese Factory. Could you tell how they made cheese then?”

Mr. Corrigan: “Yes. The men came in the morning on these wagons. These fellas got so much a hundred for raw milk. They made a tender, and the lowest tender was accepted. They had a special bottom they had on the wagons. It was all fitted for these two-hundred-and-fifty pound cans to sit in you see. And they had a rope that tied all of them on, and then they had sides out between the wheels for them to drive the hoops down, and this was out to draw the cans on. It depended on the size of the trip they had. Some of ’em would bring as much as twenty cans. That was quite a load of milk! Some of those cans would weigh, well not them all, but a few would weigh two-hundred pounds. Sometimes on Monday morning they’d have two cans. Sometimes they’d have to run an extra outfit to bring the extra cans in. When the milk came in the cheesemaker took the cans of milk… There was a crane and they had those rigs that went down and grabbed into the things on the handles of the cans, and you turned the crank and warmed the thing up, and it swung around, and you emptied it out into a tank that was on the scales, and it was weighed there. And on this tank there was troughs, and you had to put whatever vat you wanted to put the milk in, and they had a strainer. It was all strained through a cheese trough into these vats. Then you heated your milk up to a hundred-and-forty degrees, and you waited until it was right. You did it the old-fashioned way. You didn’t use an acid test like today. You took a tumbler of milk out of the vat and put so much rennet into this milk and stirred it for so many seconds and when it was right, then we set it. It was so much rennet for a hundred of milk, and you put that in, and you stirred it and got it well mixed up. And we had great–I don’t know if you’d call them “rakes” or not– a wooden affair, and they had paddles on them–four or five–and they went the depth of the vat. You turned it for so long, and then you let it set. When it was ready to cut we had knives the depth of the vat, one crosses the other. And you’d go along the vat and go up and down and cut ’em the whole way across each time and then the other way and cut across that. And you had to put in color before you put in the rennet. So then you heated it up to one-hundred-and-eighty degrees or something like that, and the curd, you had to keep stirring it. You’d use wooden rakes, and you kept stirring that for so long, then you’d let it set and then you wanted to know when to take the whey off. You heated an iron in the boiler and you took some of this curd out of the vat and you squeezed all the whey out of it, and took this curd to the hot iron and when it pulls off the iron, you let the whey out of it. Then you made a drain. You’d settle the vat with blocks under one end of the vat that you knocked out and stood the vat up like this, and then you put them under the other end, so that drained all the whey out of it. Then you put the two piles there and left it there for a while and took a big knife and you cut the end off… It all depended on what stage the milk was at. Sometimes in hot weather you’d get gases, and the work was different then. You’d take another piece of hot iron and test it again…”

Part 7

Mr. Corrigan: “A box went across the vat, and one fella was down in the bottom with pieces–you know what curd’s like, it comes out in a string and all. One fella would..[?], and the other would put the curd into the shell [?]. And then you put it in there and you tightened it up; you had a crank to turn it with. You left it there for a while, you put the salt in, you left it there for another while, and then you put it in hoops. You had pillars you see and you put your cheesecloth over this thing there, you put them down in your hoops, filled it up with curd and you put the lid on. It had to be pressed. You put it in these hoops, filled it up, then you put a wooden lid on it, and it went out on the side. And you pressed it, left them there for so long, and then you had to take them all out and dress them. You had to leave them there long enough so they were set you see. And you had these things on top of the cheese. You turned it out of the hoop, trimmed this thing off, you turned it over to the other side and the back of the hoop. And when you got that all done you put it back in the press, tightened it up good and well, washed up everything and scrubbed everything out, and the last thing you done was give this press a few extra turns, and it would stay in there ’til the next afternoon. Then you got it out, carried it out and cured it on big, wide shelves. You put the cheese on that and you weighed it; it always weighed from seventy-five to eighty-five pounds. And then you had to make the boxes to put them in. The boxes came in long strips, and you had a box beside the boiler, and you had a machine. And you had to nail the lids on the boxes with a machine. You had to make an average of at least ten or twelve boxes a day. They stayed in the curing room about three weeks. And then they were shipped, loaded in the car.”

Interviewer: “About how many people would work there?”

Mr. Corrigan: “A lot depended. When they had four vats, they had three and sometimes four. And then when they got down to two vats in later years, two lads. It was heavy work, but it was interesting. And all the passengers could get a cheese. I go over here to the bar, and I don’t get a cheese! I think they got from fifty cents to ninety cents, something like that.”

Interviewer: “And then the cheese you sold to people right around the area?”

Mr. Corrigan: “Oh yes, to anybody that… The cheesemaker wouldn’t sell it to anybody. They wanted it to go to the store. The stores always had the cheese.”

Part 8

[Mr. Corrigan goes on to talk about some personal matters.]

Mr. Corrigan: “Jenny Hodgins, that was W.A.’s sister, used to run the post office and the store, and she looked after her mother.”

“The country has all changed. There isn’t anybody that lives down where we used to live. Whey butter won’t stand up in the hot weather, but it’s very clean. It had to be right, and it never had a chance to get anything bad in it. The cheesemaker was hired; he got so much a pound for makin’ this cheese.”

Transciption by Sue Lisk