The winter of 1916 in Pontiac County and the surrounding regions was exceptionally severe. The season set in heavily when “the heaviest snowstorm known for years fell on Christmas day.” Extreme temperatures were recorded across the country; letters from former residents out West reported that it was “the coldest winter for thirty years,” with the thermometer registering 34 degrees below zero.

The harsh realities of the First World War were highly visible in the community as news of casualties arrived from the front. The community frequently mourned local men killed in action, holding memorial services for soldiers like Private David H. Hodgins.

The death of Private David H. Hodgins, on the field of honor in Flanders, for the second time within a few months, brings home to this community an acute realization of the awful struggle which is being waged on the other side of the Atlantic. The sad news of Dave’s death on March 11th (wrongly given on the 8th in our last issue) came as a great shock to the relatives here, inasmuch as on the same day as the telegram came, letters were also received from the deceased, stating that he was well, and living in expectancy of enjoying a respite from trench work in the course of a few days.

The late Pte. Hodgins, was the second son of Mr. Wm H. Hodgins of this village. Had he lived he would have completed the 40th year of his age in April. He removed to B. C. about nine or ten years ago, leaving his two youthful sons (now with the 77th Batt.) in care of relatives here. At the time of his enlistment for overseas service in the 48th Batt. of Victoria, B. C., he was foreman over a bridge construction gang on the C. N. R. Quite a number of the men enlisted at the same time. The 48th embarked for England in July last, and were under training there for several months before crossing the Channel.

Private Hodgins had served a few days over five months in the trenches when he met his fate. Before submitting to the supreme sacrifice, therefore, “his bit” in the Empire’s service had been abundantly performed.

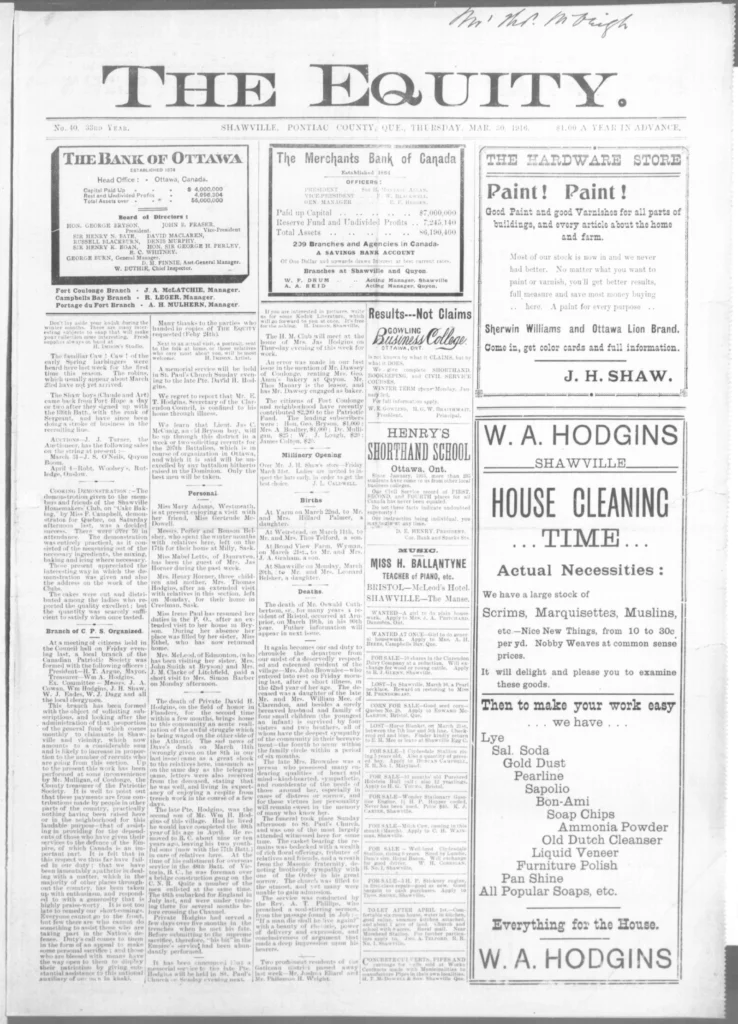

— The Equity, March 30, 1916

The papers also detailed the horrific nature of the combat and the sacrifices made by the troops, recounting stories such as that of Private James Harty, who gave his life in a “death of deliberate self-sacrifice” when he left his dug-out under heavy fire to rescue a wounded comrade.

On the home front, local residents organized to support the war effort through donations and continuous labor. The Homemakers’ Clubs were highly active in producing necessary clothing for the troops; the Bristol branch alone contributed “15 pairs wristlets… 60 handkerchiefs, 20 flannel shirts,” and numerous other hospital supplies.

Citizens also sent regular financial contributions to the Red Cross and the Patriotic Fund. Furthermore, continuous appeals were made to the public to donate to the Over-Seas Club’s tobacco fund to provide “smokes for our Canadian soldiers,” with organizers warning that the shortage of tobacco in the trenches was “appalling.”

The military actively addressed the county’s population through highly organized, localized recruiting campaigns. Recruiting officers, such as Captain Fisher, Lieutenant Bray, and Sergeant McLean, frequently visited the area to secure recruits for various overseas units, including the 130th and 136th Battalions. These efforts were marked by enthusiastic public gatherings, such as a heavily attended meeting at the Russell House, where organizers sought out “picked men” for specialized roles like painters, cyclists, and dispatch riders.

The military also leveraged local connections to encourage enlistment, sending Lieutenant James C. McCuaig, a former Bryson resident, to solicit volunteers for the 207th Battalion. Specialized units canvassed the region as well; for instance, recruiters for the Forester’s battalion came to Shawville and Campbell’s Bay looking for men experienced in cutting timber to assist with overseas trench and bridge building.

Simultaneously, the military recognized the linguistic and cultural divide by forming specific French-speaking units to appeal to French-Canadian patriotism. Lieutenant Alban de Loderriere, representing the 57th French-Canadian Battalion out of Hull, actively canvassed the Fort Coulonge vicinity and successfully enrolled local men for his unit.

On a broader provincial scale, the war effort even temporarily bridged sharp political divides. The press noted the prominent example of Olivar Asselin, a “brilliant advocate of the Nationalist creed” and former editor of Le Nationaliste, who put aside his political differences to raise and lead a French-Canadian fighting unit known as the 163rd, or “Asselin’s Battalion”.

Despite the toll of the war and the harsh winter, routine civic and agricultural life persisted. Local towns maintained an organized hockey league, and farmers gathered at the Shawville Seed Fair to inspect exhibits of “Red and White Fife Wheat” and “Banner Oats,” ensuring they had clean, high-quality seed ready for the spring planting.

Soldiers Mentioned in The Equity

Norman Smith

Mentioned: January 6, 1916

Status: He is the son of townsman Mr. Ben Smith, and he went to Ottawa to enlist with the 77th Battalion.

Ben Smith

Mentioned: January 6, 1916

Status: He is the son of townsman Mr. Ben Smith, and he went to Ottawa to enlist with the 77th Battalion.

Orval Armstrong

Mentioned: January 6, 1916, and January 27, 1916

Status: The son of Mr. Silas Armstrong of Radford, he enlisted with the 120th Battalion quartered at Lindsay, Ont.. He was later reported visiting his parents while serving with the Army Service Corps in Toronto.

Audrey Eades

Mentioned: January 6, 1916

Status: The son of Mr. W. J. Eades, he joined the mechanical transport service to be employed as a chauffeur.

“Nick” Carter

Mentioned: January 6, 1916

Status: He was a celebrated lacrosse player who played for the local team “The Rocks,” though he originally came from Elora, Ontario. He laid down his life for the Empire, dying of meningitis at the Salisbury training camp.

Captain Leon Curry

Mentioned: January 6, 1916

Status: An officer of the 42nd Canadian Battalion who was killed by a German shell within two minutes of getting into the trenches for the first time.

Wm. Elliott

Mentioned: January 13, 1916

Status: Having been in the employ of Mr. H. H. Hodgins for several years, he enlisted in the 77th Battalion.

Pte. Ernest G. Allen

Mentioned: January 13, 1916

Status: A soldier of the 77th Battalion who visited his home at Morehead accompanied by his bride.

Herbert Elliott

Mentioned: January 20, 1916

Status: The son of Mr. Thos A. Elliott of Yarm, he had been living at Lemsford, Sask., and enlisted with the 68th Battalion at Regina.

Pte. R. V. Anderson

Mentioned: January 27, 1916

Status: Serving at the front with the 21st Battalion, his wife received word that his eyes were badly affected by gas discharged by the enemy during a hot engagement.

John Hobbs

Mentioned: January 27, 1916 Status: A resident of Clarendon who went to Ottawa to enlist in the 77th Battalion.

W. Thomson

Mentioned: January 27, 1916

Status: A resident of Bryson who recently returned from Vancouver and enlisted in the 50th Battery, training at Kingston.

Fred Maxwell

Mentioned: January 27, 1916

Status: Formerly a book-keeper for G. A. Howard, he enlisted with the 88th Battalion with the rank of quarter-master sergeant.

Corporal Carey

Mentioned: January 27, 1916

Status: Serving at the front, he wrote a letter describing his experiences to his cousin, Miss E. Palmer of Starks Corners.

C. Armstrong

Mentioned: February 3, 1916

Status: The second son of Mr. and Mrs. Jas. Armstrong of Green Lake, he volunteered from the Wesleyan Theological College and was accepted into No. 9 Field Ambulance.

Frank Armstrong

Mentioned: February 3, 1916

Status: Son of Mr. and Mrs. Jas. Armstrong of Green Lake, he was already serving at the front with the 9th Field Ambulance.

Private James Harty

Mentioned: February 3, 1916

Status: He gave his life in a death of deliberate self-sacrifice, crawling out of his dug-out under heavy fire to rescue a wounded comrade.

Midshipman Howard E. Reid

Mentioned: February 10, 1916

Status: The second son of Mr. G. E. Reid of Portage du Fort, he was serving on H.M.S. “Berwick” and enjoyed a holiday at home.

Dr. Henry Argue

Mentioned: February 10, 1916

Status: The son of Mr. and Mrs. H. T. Argue, he was serving as the medical officer to a Canadian unit at the front in Flanders.

Pte. Hiram Smiley

Mentioned: February 24, 1916

Status: A soldier of the 73rd Highlanders in Montreal, he visited Shawville before his battalion departed overseas.

Lieut. F. V. Murtagh

Mentioned: February 24, 1916

Status: The son of the late Francis Murtagh of Litchfield, he served as a recruiting officer for the 156th Battalion.

Rev. Jas A. Elliott

Mentioned: March 2, 1916

Status: An old Shawville boy, he served as the Chaplain of the 136th Battalion.

William Blakely

Mentioned: March 9, 1916

Status: The son of the late William Blakely of Bristol, he was reported as being on active service.

Erwin Hodgins

Mentioned: March 9, 1916

Status: The eldest son of Mr. and Mrs. W. E. Hodgins of Yarm, he enlisted under Capt. Fisher of the 136th Battalion in Cobourg.

136th Battalion Recruits

Mentioned: March 16, 1916

Status: A published list of Pontiac men who signed up with Capt. Fisher of the 136th Battalion included: William Buck, George Munro, Charles Reaney, Will Tolbert, Wm. Hobbs, Tassem Beck, John Williams, John Young, Alex. Yorclet, L. Perrault, A. St. Denis, H. J. Wiggins, John Anderson, Roy Danis, Don Doherty, T. A. Orr, Robt. McMahon, H. Bronson, Robert Laird, Milton Rutledge, F. Stewart, W. D. Dagg, C. Hoolihan, Patrick Allen, Syl Hoolihan, M. D. Allen, S. T. Hodgins, R. T. McConnell, Chas. McKay, W. M. Russell, S. Halligan, Henry Gilpin, W. Sheppard, Wm. Emmerson, Pat. Gilbertin, and Jas. Killoran.

Lieut. Alban de Loderriere

Mentioned: March 23, 1916

Status: Formerly a provincial organizer for the I.O.F., he successfully recruited 15 local men in Fort Coulonge for the 57th French-Canadian Battalion

Sergeant Claude Shaw

Mentioned: March 30, 1916

Status: He returned from Port Hope to Shawville after signing up with the 136th Battalion, holding the rank of Sergeant, and assisted in recruiting.

Sergeant Arthur Shaw

Mentioned: March 30, 1916

Status: Like his brother Claude, he returned to Shawville with the rank of Sergeant after signing up with the 136th Battalion to assist in recruiting.

Lieut. James C. McCuaig

Mentioned: March 30, 1916

Status: Described as an old Bryson boy, he was scheduled to solicit recruits in the district for the 207th Battalion.

Private David H. Hodgins

Mentioned: March 30, 1916

Status: A resident of Shawville who was killed in action in Flanders on March 11th, leaving behind a bereaved wife and four small children. He met his fate after serving a little over five months in the trenches.

Emmerson Paul

Mentioned: March 30, 1916

Status: The eldest son of Mr. Thomas Paul of Bryson, he donned the khaki and was sent to the front early after carrying off first honors in a shooting and signalling competition in England.

Raymond Horner

Mentioned: March 30, 1916

Status: The son of J. B. Horner, formerly of Clarendon, he joined Lt.-Col. Lightfoot’s 101st Battalion.

Garfield Horner

Mentioned: March 30, 1916

Status: The son of J. B. Horner, formerly of Clarendon, he also joined Lt.-Col. Lightfoot’s 101st Battalion.

Listen to our Podcast!

We’ve used Artificial Intelligence to summarize what was covered in The Equity during this part of the Great War. Click the play button to listen.

Timelines: January - March 1916

Read more from the pages of The Equity! Click any of the issues below and download a PDF version of that week’s issue.